The scientific hypothesis

Finding the cause

The ambitious aim of Jean Seignalet’s approach is to tackle the causes of chronic disease rather than their symptomatic expression. The answers to the question "Why am I ill?" often revolve around symptoms: "Such and such a mechanism doesn’t work properly any more” or around genetics: "The cause is hereditary", which implies that nothing can be done. These 2 statements are real but inadequate. They express the incapacity of today’s medicine to answer the essential question: "Why does my body suddenly start to malfunction after years of good and loyal service?".

The ambitious aim of Jean Seignalet’s approach is to tackle the causes of chronic disease rather than their symptomatic expression. The answers to the question "Why am I ill?" often revolve around symptoms: "Such and such a mechanism doesn’t work properly any more” or around genetics: "The cause is hereditary", which implies that nothing can be done. These 2 statements are real but inadequate. They express the incapacity of today’s medicine to answer the essential question: "Why does my body suddenly start to malfunction after years of good and loyal service?".

If the answer was essentially found in genetics, the disease would be triggered from birth. The inherited terrain is an important factor because it defines how susceptible a person is to contracting such or such a disease but the other factors in play must be environmental in origin.

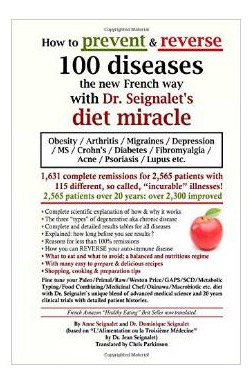

There are many environmental factors that can act on health (all types of pollution, tobacco and stress etc.) but Jean Seignalet puts the modern diet at the centre of his hypotheses of pathogenesis. He is the first to propose a complete disease mechanism for chronic disease (91 diseases) going from the basis to the first symptoms. He is supported by the most recent discoveries in the field of biology, genetics and immunology where he was one of the world’s leading specialists.

His scientific hypotheses cannot fall far short of reality because his dietary method is very effective. To date, no medicine and no therapy have succeeded in warding off the development of these diseases. In a group of several hundred people, a single remission in just one of the incurable diseases he treated is a tour de force in itself. The success of his therapy, even if there are failures in diseases that still respond to the hypotoxic diet, is far superior to a simple isolated one-off success. The efficacy of his method is far superior even to the results obtained by conventional medicine over a large number of diseases. It can easily be verified, involves no risk and is compatible with allopathic treatments and with alternative medicine.

Scientific hypothesis

The 3 types of mechanisms involved in chronic disease that Jean Seignalet discovered involve the function of the small intestine, (intestinal hyperpermeability) and enzymes. Stress also has a role to play. The basic ideas behind his theories are summarised below in a few lines. Making complex hypotheses accessible inevitably involves approximations.

Modern diet and enzymes

Most chemical reactions in our body depend on the 1,500 enzymes we possess. They each have a specific form and function. For Jean Seignalet, the enzyme catalogue of every individual is variable, unequal even. In some genetically predisposed people, the enzymes have no opportunity to adapt to molecules that are “against nature”. The latter persist in the small intestine resulting in putrefaction of the intestinal flora and weaken the wall of what is rightly known as the “intestinal barrier”.

Human enzymes were well adapted to the natural ancestral diet made up of raw products. In addition, our ancestors consumed this diet for millions of years. The modern diet, initiated on settlement and the advent of agriculture has undergone more changes in the 20th century than during these last 5,000 years. The proportion of substances that are “unbreakable” by enzymes during digestion has multiplied. To establish a healthy small intestine it makes sense to return to a diet similar to that our ancestors enjoyed by excluding, for sound scientific reasons, foods that are potentially harmful.

The small intestine and hyperpermeability (Leaky gut)

To exert their harmful effects, agents originating from outside the body have to penetrate its interior. However, they find it difficult to pass through the skin or much of the mucosae which are made up of several layers of cells and are too impenetrable.

Only two mucosae appear to be weak because they extend over a large area and are very thin. These are the mucosae of the pulmonary alveoli and the small intestine. The majority of these harmful molecules penetrate the small intestinal mucosa and a minority enter via the epithelium of the pulmonary alveoli. It is important to remember that the small intestinal mucosa has an area of 100 square metres and a thickness of 1/40 of a millimetre and is made from just one layer of cells.

The small intestinal mucosa has a major influence on our health. Depending on whether or not this barrier has maintained its impermeability, dangerous molecules can or cannot pass into our bloodstream.

In fact, the small intestinal mucosa acts as a barrier between the internal milieu of the human body and dangerous environmental factors, bacteria and, for Jean Seignalet, unnatural foods as well.

In certain individuals, the barrier fails to play its role properly and lets too many macromolecules through. The mucosa is transformed into a sieve, through which dangerous molecules enter the general circulation:

- bacterial molecules: peptides, DNA, lipopolysaccharides and polyamines,

- food molecules: peptides, proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and Maillard compounds created by cooking.

The composition of these molecules varies from one subject to another, because it depends on the intestinal flora, what we eat and the enzymes which act on proteins, lipids and carbohydrates at different sites. According to their structure, these molecules have an affinity with such or such type of cell or tissue in our body and, in some people, they cause disease.

The stress factor

Stress aggravates small intestinal hyperpermeability by causing interferon-gamma secretion. This mediator attaches to the cells of the intestinal mucous pushing them apart. Stress often plays a part in triggering the initial outbreak and later outbreaks of various diseases observed by Dr Seignalet.

One of the main mechanisms operates as follows. In stress, the neurons release neuropeptides. These messengers activate the cells that produce interferon-gamma. This mediator attaches to the enterocyte membrane pushing them apart thus allowing a far higher quantity of waste to enter the body which triggers the outbreak of disease.